Nov

20

In Describing Mormonism, Who Is More Accurate: Believers or Reporters?

November 20, 2007 | 51 Comments

A heated digital discussion following last week’s review of Dick and Joan Ostling’s Mormon America on this site brought up a set of pointed questions about religion and journalism.

A heated digital discussion following last week’s review of Dick and Joan Ostling’s Mormon America on this site brought up a set of pointed questions about religion and journalism.

Commenter Amanda P. wrote: “If you are interested in Mormonism, visit mormon.org and get your answers straight from the Church itself. This book is NOT an ‘objective’ point of view.”

To which commenter Henry James replied: “Re: the ‘mormon.org’ suggestion. [That] is an official Mormon web site, hardly the place to go for ‘objective’ information. [That’s] like going to MerrillLynch.org for the objective information on their regime change.”

As an old-school journalist (i.e. one born before 1980), RW’s sympathies lie with Henry James on this point. A reporter cannot cover the war on terror, for example, only by quoting Pentagon press releases. Rather, a reporter has to get out there and dig up hard information, seeking multiple points of view and documentary evidence when possible.

This was the approach of the Ostlings, it seems to RW, as they drew on the works of both Mormon, non-Mormon and ex-Mormon scholars in researching their books. They demonstrated that the church squelches alternative points of view among members, sometimes using excommunication or other punishments. The Ostlings write that, of course, “ecclesiastical censure as such is nothing unusual. Most religions have some form of discipline on the books, usually to deal with moral misconduct.” They continue:

The LDS Church, however, is unusual in penalizing members for merely criticizing officialdom or for publishing truthful — if uncomfortable — information.

If freedom of information is at question, then, the call to refer back to official church websites for an objective perspective rings somewhat hollow. Mormon.org, for example, does not mention anywhere the Mormon scholars the Ostlings interviewed, who were excommunicated in the 1990s for their academic work on the faith.

“Islam is Peace”

But if you really want to understand a faith, shouldn’t believers themselves offer the most definitive answers for curious outsiders? Do religious groups have a right to “media self-determination?”

The answer, in RW’s view, is yes and no. Following 9/11, for example, American Muslims have come forward to explain, time and again, the basics of Islamic faith and how terrorism is contrary to Islamic teachings. Such assertions from Muslims, however true, tend to exasperate fellow Americans largely, RW believes, because these “explanations” of the faith do not answer the central question of how 19 Muslim men could believe God wanted them to perpetrate the crimes of 9/11. Americans aren’t so interested in the details of Ramadan fasting or Muslim charitable giving — they need to know about the connection between Islam and terrorism.

Who Gets to Answer: “Are Mormons Christians?”

Just so, non-Mormon Americans have some central questions about Mormonism. One of the most oft-talked about is the question, “Are Mormons Christians?” And here is where the clash of perspectives between inside believers and outside observers really starts to generate sparks.

Both Mormon leaders and individual believers are quick to say they are Christians — they believe in Jesus Christ as Lord and await His Second Coming. Shouldn’t that be the end of it? Aren’t people allowed to define themselves? Again an analogy from Islam: Groups such as the Ismailis and Ahmadiyyas consider themselves Muslims, even while Sunni and sometimes Shia Muslims reject that idea and sometimes even persecute these groups. How should a reporter or other outside observer handle this question? Do you take a faith group at their word, do you listen to their rivals, or do you try to average between the two points of view?

One thing that both sides on the Mormon discussion should realize is there are no simple answers to these questions. Critics who assert that Mormons are not Christians must acknowledge the right of people to define their own beliefs; indeed, self-definition is an underpinning to American religious freedom. But just so, Mormons must realize there is a limit to the authority of self-definition. A believer insisting that “Mormons are Christians, period,” is somewhat like a Muslim believer saying, “Islam means peace, period.” In other words, there are some other issues to address. And one of these is the fact that the very idea of the “restored priesthood” in the Church of Latter-day Saints negates the validity of other Christian churches.

The Ostlings recount this story in their book:

A Mormon guiding a friend through the Salt Lake City visitors’ center in Temple Square asked, with tears in her eyes, ‘Why do so many people say we are not Christians? How can they, when the Savior is central to our faith?’ The friend paused and then responded, ‘But do you truly regard non-Mormon believers as fully Christian?’ The Mormon, seemingly unaware of the quid pro quo in her answer, exclaimed, ‘But that’s because we have the priesthood!’

Perhaps the most interesting new contribution to this are-Mormon-Christians discussion came last month from Richard Land, a leader of the Southern Baptist Convention, who said he considers Mormonism “the fourth Abrahamic religion-Judaism being the first, Christianity being the second, Islam being the third and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints being the fourth.” Land, who is supporting GOP presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, is a sympathetic outsider, trying to build a bridge to Romney across which his fellow evangelicals can walk. Will Mormon leaders and believers accept his definition?

**Your Questions for the Ostlings**

RW is currently seeking an interview with the Ostlings for this site, and she will gladly pose to them questions that readers suggest below in the comments section.

ReligionWriter also wishes you a happy Thanksgiving holiday.

Sep

17

“To Make an Enemy of 500 Million People is Ludicrous”

September 17, 2007 | 3 Comments

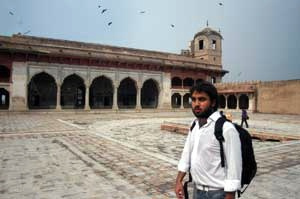

In the last post, ReligionWriter was speaking with video and text blogger Amar Bakshi about the religious ideas he found while traveling in Britain.

In this segment, Bakshi shares the insights he gained as a roving blogger in Pakistan to explain why Osama bin Laden is so popular there, and how differing perceptions of his own religiosity affected his reporting.

In this segment, Bakshi shares the insights he gained as a roving blogger in Pakistan to explain why Osama bin Laden is so popular there, and how differing perceptions of his own religiosity affected his reporting.

ReligionWriter: A poll this month found that Osama bin Laden has a 46% approval rating in Pakistan, making him more popular than Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf (38% approval rating among Pakistanis) and U.S. President Bush (9%.) To most Americans, those numbers for Bin Laden seem absolutely horrifying. What would you say to help Americans make sense of them?

To some of the people I spoke with, Osama bin Laden represents slap in the face of

In Pakistan, as in many countries besides the U.S., historical memory, and the mythologization of that memory, is very powerful; Pakistanis well-remember America’s involvement in the rule of [former military leader] Zia ul Haqq. Ironically, they are objecting to the radicalization of Islam and the loss of liberty that his rule entailed — in a convoluted way, that is associated with America in the minds of Pakistanis. There are similar analogies in Iran.

RW: Is anyone who supports Osama bin Laden necessarily a violent enemy of America? Is it possible to humanize that bin Laden supporter? Is there any common ground to work with?

Bakshi: The whole pursuit of “How The World Sees America” — and for some people, I’ve learned, my approach is quite controversial — is to humanize these guys. How are you going to say 46 percent of a country of 160 million are fundamental enemies? That’s ridiculous. If you go to other countries, the numbers are just as staggering, if not more so.

To make an enemy, in our minds, of 300 or 500 million dispersed people is ludicrous. So you’re going to have to humanize. I can see the headline: ‘Humanizing Bin Laden Lovers.” Put that way, you can just dismiss the idea, but that’s far too simplistic.

There is a huge spectrum of what that support actually means. Would any of these guys lay down their lives for him? If you ask that in a poll question, I don’t think the number would be high. So what does it mean to them to support someone like bin Laden? And what is it they are searching for? These types of questions usually have very personal answers. That’s very much what this project is about: what are those personal answers?

RW: Do you mean everyone has a story like “a CIA agent killed my brother?”

Bakshi: Each act that takes place affects 100 people around that act. Social networking thought might help here. When one person dies in

Then, of course, anti-Americanism is very much exploited by political parties, by imams wanting more power or prestige, or in organizations where anti-Americanism is a way of expressing belonging. So you might start with a rational reason for disliking America — maybe a CIA agent really did kill your brother — but this drumming up of hype can quickly lead things to spiral into the irrational.

There are two things at work here. First, we have got to figure out what policies of ours might be dangerous for us in terms of perceptions in the long term. I think that’s an important consideration, and one that we can control. Then we have to see some things for what they are: for example, political infighting in which orthodox people attack moderates by claiming they are pro-America. Really that has nothing to do with America, it’s really about moderates and extremists battling each other within their own society.

RW: Tell us a little about your own religious and cultural background. What sort of Hinduism were you raised with?

Bakshi: I went to Episcopal school, St. Albans, where I was on the vestry. My mother is a spiritual woman, but no one in my family is particularly religious. To me, religion is a way of ordering your spirituality, of disciplining it. The idea is a certain practice gets your spirituality richer or better.

I have been free to dabble in a lot of different things and read a lot of books, both as literature and for teasing out how to live life. In terms of what practice I want to use to discipline my spirituality, I haven’t decided yet, but I’m not opposed to picking one eventually.

If anything, my family is Hindu, but there are Muslim influences as well, and of course I went to Christian school, and my mother tried to send me to Hebrew school -

RW: Hebrew school?

Bakshi: I was young, and at the time, my mother thought it was a just beautiful language, with beautiful stories, and she always dreamed of going to Jerusalem. She still does.

RW: You were born and raised in Washington D.C. Before you went to India for your blog, had you been to there before?

Bakshi: Growing up my mother never really wanted me to see India or learn Hindi. My parents had just recently migrated to the U.S., they were struggling to fit in, and my mother was fighting her own gender war to define herself as a physician, and she thought Indian culture didn’t help her in that. But when I was 15 I went back to India when my mother set up a local scholarship for a girl in Mysore, where she was from. I got really interested in local crafts people and set up something called Aina Arts, which links crafts people up with art markets.

RW: You are often mistaken for a Muslim. How has that experience affected you and your reporting?

Bakshi: One reason I don’t want to talk much about my religion online is that I love being mistaken for any number of things. In Latin America, I’m taken for Latin American. When I introduce myself to Muslims, I’m assumed to be Muslim, and Hindus assume I’m Hindu; I know enough about each to hold my own.

I go to a lot of Muslim services around the world, wherever I am. It’s a great way to connect and meet people, and I don’t feel badly doing it.

RW: You mean you would go to Friday prayer at a mosque and pray yourself? As part of your reporting for the blog?

Bakshi: Yes. (Laughs.) I have gone to Friday prayer and prayed, often out of sign of respect; I would be with a bunch of people who were going to pray, and it seemed rude to say, “I’ll wait outside.” In high school, I said the prayers every day, and I wasn’t Christian. I was head prefect of my school for a while, and at every ceremony I had to give a prayer, which I ended with “Amen.” One teacher told me it was just a sign of respect.

So that’s how I interpret it. [Blending in] helps me meet a lot of people, and I earn a lot of trust as a result of being ambiguous. I have no hesitation about that, because ultimately I think it’s foolish for there to be divides on the basis of religion, and I’m perfectly happy moving between them.

RW: So you go to a madrassa in South Asia and act like a Muslim, salaam aleikum and all that, and later they find out you’re not officially a Muslim: What happens next?

Bakshi: I never lie. If someone asks me “what are you,” I say exactly what I told you: my parents are Hindu but they are spiritual; I have devout Muslim and Sikh ancestors not that far back; I went to a Christian school, and basically I haven’t decided for myself yet.

I’ll be around the most hard-core Muslim guys you can imagine, and all they’ll say to me is:”Look, brother, this is not a good way to be, you have to choose.” They won’t say, “You snuck into our mosque, how dare you.” I’m happy to have them present to me the values they find in their faith. If anything, that’s when their passion really comes out.

Sep

14

British Divided Over Religion’s Role in Public Life: Q+A with Amar Bakshi

September 14, 2007 | 1 Comment

Amar Bakshi has what for many people would be a dream job: the 23-year-old recent college graduate travels the world, capturing the thoughts of ordinary and not-so-ordinary people in word and image. Bakshi’s text and video blog, “How The World Sees America,” appears on Washington.Post.Newsweek.Interactive’s foreign affairs blog, Post Global. This summer, Bakshi traveled to England, Pakistan and India. He’s briefly back in his hometown of Washington D.C. before heading off to the Middle East, South East Asia and Latin America in October.

ReligionWriter caught up with Bakshi this week to ask him what role religion plays in perceptions of America and how he manages his own “ambiguous” religious identity while traveling. Part One of the interview appears today; Part Two will appear on Monday.

ReligionWriter: How did you manage to create this assignment for yourself?

Amar Bakshi: I always wanted to see more of what life was like in places where headlines were happening. CNN clips are nice, but they’re short, and I never could figure out, say, what the woman in the background’s life was all about. I was working on Post Global, and I first pitched the idea of doing something on ordinary lives through text and video. What the project needed, though, was an overriding question that would hold it all together.

Amar Bakshi: I always wanted to see more of what life was like in places where headlines were happening. CNN clips are nice, but they’re short, and I never could figure out, say, what the woman in the background’s life was all about. I was working on Post Global, and I first pitched the idea of doing something on ordinary lives through text and video. What the project needed, though, was an overriding question that would hold it all together.

At the time I was still wrestling with my experience in

RW: When people overseas look at America, do they perceive it as a religious nation?

Bakshi: I’d have to say no. Religiosity in the

RW: So when people overseas think of America in religious terms, they only think of the religious right?

Bakshi: Yes, but there is also a good sense of the religious diversity that

RW: We hear that Europeans tend to see Americans as crazed religious fanatics. Did you get that sense from the British people you met?

Bakshi: In England I heard again and again a feeling of surprise at how overtly patriotic and outspokenly religious Americans seem to be. The two ideas were often conflated, especially when it comes to perceptions of U.S. foreign policy. But in England at least, people spoke with some nuance about different aspects of American religious life, rather than lumping everyone together.

RW: England is known for being much less religious than America; we hear about Anglican churches with only a handful of elderly ladies in the pews. Did you find that to be true?

Bakshi: Public display in general is much more of an American characteristic than a British one, and this applies both to patriotism and religion.

There’s a sense around England, “If only we were less demonstrative of our beliefs, the better we could all fit into this polity.” When Jack Straw, the home minister, asked a woman to remove her face veil, there was a huge uproar, but his point was wanting to lessen those differences in public as much as possible.

RW: I have heard that British Muslims are more outwardly traditional-looking than American Muslims — that you’re more likely to see women with face veils or South Asian men in salwar khameez for example. Did you find that to be true?

Bakshi: It’s one of the first things I noticed when I got to Walthamstow or Blackburn. You walk down the street and there are bearded guys everywhere; you could be on a street in Lahore or Malegaon in India. But at the same time, there are a tremendous number of British Muslims who look just like I do, and I’m not terribly religious at all. So it’s easy to get fixated on those strong outward displays of identity.

In Blackburn, what I heard is this: outward displays help to bind together a community that felt itself under seige; identifying marks help them remember what they are fighting for. Of course everyone has a different explanation of what that is.

RW: And why exactly do British Muslims feel under siege?

Bakshi: The grievances of most were largely not religious but civil liberties-oriented grievances. I heard again and again the idea that “our friends are getting jailed, we’re scared, we don’t have jobs, there’s crime.” It wasn’t “the West is too liberal” or “Christianity is at war with Islam.” Of course there is a small minority of extremists that do hold those views, but they are not held by anywhere near a majority of British Muslims.

RW: Do you think emphasizing America’s religiosity is a way to build bridges with Muslims or others worldwide who would otherwise be anti-American?

Bakshi: Absolutely. In

On the other hand, the people who don’t want religion in public life, who think religious displays should be tamed down, for them America’s religious center is not really seen as an ally. It’s seen as a problem of religion growing into the public sphere. In England in particular, I heard the sentiment that religious expression needs to be reigned in.

Coming Monday: Bakshi offers explanations of why Osama bin Laden is more popular than President Musharraf in Pakistan, and how his own fluid religious identity has impacted his reporting.

Sep

11

Hey, Journalists: How Not to Cover Ramadan

September 11, 2007 | 5 Comments

With the Muslim holy month of Ramadan starting at sunset tomorrow night, religion reporters around the country are already scratching their heads, trying to think up a fresh angle on a holiday that, like most, happens pretty much the same way every year. (Photo: Teens at a Ramadan fast-breaking, or iftar)

With the Muslim holy month of Ramadan starting at sunset tomorrow night, religion reporters around the country are already scratching their heads, trying to think up a fresh angle on a holiday that, like most, happens pretty much the same way every year. (Photo: Teens at a Ramadan fast-breaking, or iftar)

We are sure to see, especially in smaller-market news outlets, lots of “Ramadan 101″ stories. These pretty much write themselves:

Headline: Area Muslim teens keep the faith during Ramadan

Lede: Rayyan Abdel-Latif, 16, will be running at her Springfield High School track meet this Saturday, but she will have a unique hurdle to overcome. In keeping with her Muslim faith, Abdel-Latif, whose parents emigrated from Jordan before she was born, will be fasting during daylight hours on Saturday and throughout the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. “It seems like fasting is hard, but really God said it is not a hardship for us,” said Abdel-Latif.

Nut graf: With the holy month beginning at sunset tomorrow night, Springfield-area Muslims, which number an estimated 5,000 according to the Islamic Society of Springfield, will be swearing off not only food but drink, smoking and other luxuries during daylight hours. Not just a physical test, Ramadan is about food, family and faith, say local Muslims.

Photo: Abdel-Latif smiling in headscarf

These types of articles, of course, serve an important purpose, informing those who don’t have a clue what Ramadan or Islam is all about. Given that so many Americans have an unfavorable view of Islam (39% in 2004, according to the Pew Research Center,) just offering a basic primer on belief and practice is worthwhile. At the same time, however, this type of coverage runs two risks:

1. It can be boring (Imagine: “Area Christians celebrate Jesus’ birth with food, family and faith,”) and

2. It can dramatically oversimplify the lives of Muslims in the U.S., with unintended negative results.

The solution to both of these problems lies in journalists finding more complex story angles and drawing from a wider variety of sources. If one read or heard or saw only “basic primer” stories on Islam/Ramadan, one would get the misleading impression that American Muslims are, by definition, enthusiastically observant of their religion.

The problem here is sources: When a journalist needs to find Muslims to interview, where do they go? To mosque, Islamic school or local Muslim organization. And who do they find through such channels? Observant mosque-going Muslims. While such observant über-Muslims make perfect interview subjects if you want to explain the traditional rules governing Ramadan — because those Muslim follow those all rules — they are not representative. The May, 2007, study of American Muslims by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life had this finding:

Nearly one -quarter (23%) of Muslim Americans have a high level of religious commitment, which is defined as attending mosque at least once a week, praying all five salah every day, and reporting that religion is “very important” in their lives. About as many (26%) have a relatively low level of religious commitment, rarely engaging in these practices and generally regarding religion as less important in their lives. A majority of American Muslims (51%) fall somewhere in between.

Journalists need to be aware that mosques and Islamic schools tend to have vetted, designated spokespeople (ReligionWriter knows — she used to be one of them) who will give an orthodox interpretation of Muslim life. This is not to suggest Muslim organizations are doing something wrong — they are doing their best to receive the press coverage they want, and most other religious organizations do the same.

The point is that journalists who call up a mosque asking for sources on Ramadan are likely to interviewing the top one-percent most religious Muslims. This gives people the false impression that Muslims are extremely religious. And it’s a short jump, of course, from”extremely religious” to “fanatical.”

So how do you find more representative sources? ReligionWriter offers these tips:

Fall back on the journalist’s oldest trick: interviewing your taxi driver. In many cities, as often as not, this person will be a Muslim immigrant. Ask in a casual way about what he (okay, or she) likes about Ramadan, how it’s celebrated here in the U.S. versus his home country.

Use social networking: It’s not journalistic-ly haraam, in ReligionWriter’s view, to find sources through friends and acquaintances. Do you have a neighbor with a Muslim-sounding name? Have you ever noticed how many Muslims people and Muslim interest groups are on Facebook?

Interview people, not their religion: Make your sources feel you are interesting in finding out how they personally practice Islam or celebrate Ramadan. If you give the impression you want them to represent their religion to the entire (and often hostile) American people, then you’re more likely to get defensive, apologetic, orthodox answers.

Read the Muslim press: You’ve got lots to choose from now, including Altmuslim.com, TheAmericanMuslim.org, Naseeb Vibes, Islamica Magazine, Illume Magazine, Muslim Girl Magazine, Azizah Magazine, Sisters Magazine, or your local Muslim newspaper (if you live near a relatively large Muslim community, there probably is one. In the D.C.-area, it’s the Muslim Link.) And this is not even to mention Muslim blog aggregation sites, like Hadithuna, or popular Muslim social networking sites like Naseeb.com.

The great thing about reading the Muslim press is that journalists will get a feel for the internal debates in the Muslim community, which are often quite different from debates non-Muslim have about Muslims. For example, “Are all Muslims terrorists?” is not a big conversation-starter among Muslims. However, ask an American Muslim about whether “halal” meat is really halal, whether ethnicity should factor into choosing your spouse, and whether the Nation of Islam made any positive contributions to Islam in America, and you’ll get a conversation going pretty quick. ReligionWriter applauds how American journalists have covered the intense intra-Muslim debate about marking the beginning and end of Ramadan.

As altmuslim.com founder and editor, Shahed Amanullah, said in a Beliefnet interview with Omar Sacirbey last year:

It’s good that America sees [Muslim internal debate] because one of the fears Americans have about American Muslims is that we’re automatons that do what people tell us to do. When Americans see our internal debates, I think that reassures them that we’re human, and we’re trying to resolve our issues.

So, to close this out, here are ReligionWriter’s story suggestions for this year’s Ramadan:

Ramadan when you aren’t fasting: Many Muslims are do not fast during Ramadan because of chronic illnesses such as diabetes. What’s it like to be around observant Muslims all month when you can’t fast yourself? Do you feel left out?

Fasting while pregnant or breastfeeding: Talk about a hot topic; Muslim women debate this one heatedly every year. Some say Islamic law allows all pregnant or nursing women to forgo fasting, others say that dispensation is only allowed in certain situations. Some women face peer pressure to fast while pregnant (”Back in Egypt, all the pregnant women fast!” “My Muslim doctor told me it was fine to fast!”) Is there any data on the safety of fasting while pregnant?

Fasting when it’s the only way you observe Islam: Many Muslims do not offer five daily prayers, dress modestly, or attend their local mosques. For some non-observant Muslims, however, Ramadan is a special time to get back to God — they may throw away the alcohol in their homes during Ramadan, try not to smoke, and observe some if not all of the fasting. Headline possibility: Ramadan for slackers.

Fasting while menstruating: A topic not for the faint of heart, and you’d do better if you were a woman reporter. But still, it’s a good story because it gets to the heart of modern views of classical Islamic tradition, which holds that women should not pray or fast while menstruating. Why not call up Irshad Manji or Asra Nomani and see what they have to say about this? The Prophet Muhammed reportedly said that women are “deficient” in their religious worship because of this exception for their menstrual periods.

And for photos: How about something besides a girl in a headscarf or men bending over in prayer!

Aug

27

The Moral Lives of Foreign Correspondents

August 27, 2007 | Leave a Comment

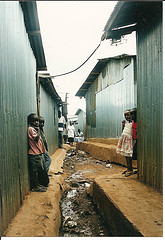

Visiting a slum in Nairobi is like walking through a haunted house: a horror around every corner. You have to step carefully to avoid slipping into the open sewers. You see and hear and smell that people are living in situations very close to hell on earth. It’s hard to fight the overwhelming urge to get in a car, lock the doors and drive fast in the other direction.

Visiting a slum in Nairobi is like walking through a haunted house: a horror around every corner. You have to step carefully to avoid slipping into the open sewers. You see and hear and smell that people are living in situations very close to hell on earth. It’s hard to fight the overwhelming urge to get in a car, lock the doors and drive fast in the other direction.

In her sensitive first novel, Mercy, out next month from Other Press, author Lara Santoro describes, through her protagonist, Anna, what it’s like to spend the night in Korogocho, one of Nairobi’s many slums:

I tried to sleep but the sound of coughing kept me up all night: coughing from a million directions, all of it so close, so intrusively maddeningly close. More than once I had to resist the urge to stand up and scream at everyone to shut up. … All of the walking around earlier in the day-the bile, the blood, the corpse-strewn pathways, the rigid muteness of people consumed by the virus-all of it failed to give me the true measure of Korogocho’s madness. Beyond the hunger, the filth, the violence, beyond the trauma of constant loss was the insanity of overcrowding.

Anna, a foreign correspondent for an American newspaper is visiting this slum to report on the ravages of the AIDS virus. The very next night, she finds herself at a fancy cocktail party across town in the company of her lover, Nick: “The perfect alignment of his teeth, the frivolity of his white linen shirt were obvious antidotes to Korogocho’s pain.” Strung between these two worlds, seeking refuge in alcohol, Anna ends the night shouting at a stranger, slapping her lover and stamping off into the darkness by herself. The raw chasm between have and have-not brings her down into her own darkness.

Anna is a wild character. She drinks too much, cheats on her boyfriend, lies to her boss, going so far as to fabricate a coup attempt in Nigeria to escape another moment in Nairobi with her cuckolded boyfriend. Anna is a fallen creature, seemingly unable to get her life together, and yet driven forward by a full-bodied desire to make moral sense of the world. She risks her life interviewing a war criminal so she can plumb the depths of his empty eyes; she makes late-night calls to an Italian priest who works in the slums, seeking absolution.

What Santoro so ably captures in her novel is the despairing wildness that results from witnessing human horrors first hand and being unable to avert them. Anna recalls covering a famine in South Sudan: She and her photographer are watching a starving Sudanese boy crawl across the desert landscape on his hands and knees, looking futilely for sustenance.

The boy is inching forward in the dust and this time I can’t help myself. I kneel in front of him and put a small carton of juice to his lips. Gerard, my photographer on this trip, catches me just in time. “Are you crazy?” he yells, galloping toward me. “Give him all that sugar and he will die!” I stand back, horrified. The boy lets out an animal wail, his eyes filled with tears.

But of course the foreign correspondent does have the tools to alleviate this suffering, right? By writing an article, taking a photo, filming a scene, correspondents can stir the rest of the world to action. But correspondents in Africa face a special problem: the Western public has only so much attention for the tragedies they cover.

Anna’s boyfriend, Michael (based on Santoro’s real-life boyfriend, Associated Press producer Myles Tierney, who was killed on the job in Sierra Leone in 1999,) recalls bitterly watching a small boy clinging to his dead mother’s body in an unnamed African conflict. When Michael tries to pick up the boy, the boy begins scream, and an aid worker comes over to yell at Michael:

Now everyone’s yelling and the kid’s crying and I’m so fucking angry I’m stiff, you know, I’m out of control….You know why? Because London’s telling me to pack up and get out: none of the networks are picking up our shit anymore. It’s Africa. No one cares. No one gives a shit. I tell Angela: ‘Wait a minute: there’s no peace agreement, there’s practically constant gunfire.’ And you know what she says? She says: ‘We’re short of people for the German elections.’

But what if you could help one person, just like the boy in that hackneyed inspirational story about throwing starfish into the sea? Anna’s chance comes in the form of her housemaid, Mercy, an intimidating woman from the slums, a mother and former prostitute, who gives some stability to Anna’s chaotic, gin-drenched life. When Anna discovers that Mercy has AIDS, she fights to get her life-saving antiretroviral treatments, which she would otherwise not be able to afford.

But even being a life-saver is not so simple. After yelling at Mercy one afternoon, Anna meditates on the fact that she literally has life-or-death power over Mercy — able to deliver the treatments or withhold them — and that even this well-intentioned power can corrupt.

Anna sees the stark outlines of her power as a “rich” foreigner when she is bullying a local doctor into okaying Mercy’s antiretroviral course before it’s too late. The overburdened doctor, working long hours at night to process test results for other HIV and AIDS patients, shouts at her:

Tell me: Is she the only one? In this country we are losing seven hundred people a day to this disease! Seven hundred people a day! Now because this woman is your friend, because she is the friend of an mzungu [white person] I must hurry! And the others? Standing in line quietly? Must I carry them to their graves?

Anna finds some moral clarity only when Mercy herself, arising from her deathbed by the grace of antiretrovirals, begins to fight the injustice around her. She starts a movement, leading hundreds of thousands of Kenyans to demand affordable AIDS treatment. Mercy represents what every outsider feels is the only true solution to some of Africa’s worst problems: having Africans themselves stand up and demand something better.

What is disappointing for the reader, however, is that we are left wondering about Anna’s own inner demons and inner divinity. She becomes subsumed in Mercy’s noble struggle, but is that enough? What happens when Mercy is gone?

Ultimately we want to know from Anna how to live on this planet, where slums rub up against cocktail parties, where the death of a boy’s mother is not headline news, where broken souls hurt one another in spite of their love.

Although the book ends movingly with a quotation from Corinthians, it is perhaps best summarized by words spoken by Anna’s friend Kez, a fellow journalist, coke addict, and devout Muslim: “Allah is great. You’re not. End of story.”

Aug

1

Is the Abortion Debate Obsolete? Q+A with Liza Mundy

August 1, 2007 | 1 Comment

The complex ethical issues of assisted reproduction explored in reporter Liza Mundy’s new book, Everything Conceivable, (and reviewed earlier this week on this site) can make the abortion debate look outdated. ReligionWriter called up Mundy to discuss the new meanings of “reproductive choice,” the voice of religious leaders in answering these ethical questions, and what the U.S. can learn from the U.K. about encouraging public debate on reproductive technology.

ReligionWriter: What drew you to the topic of fertility medicine?

Liza Mundy: I came of age in the early 1980s, when reproductive rights was an almost defining ideological issue. The word “choice” really had one meaning: your position on what a woman could do with an unwanted pregnancy. I’ve written all my career about reproductive politics, including what turned out to be a controversial article about two deaf lesbian women seeking a deaf sperm donor, which introduced me to the field of bioethics. Then I wrote about how low-income people experience infertility in 2003 and learned how common infertility is and how hard people will work to have a child.

Liza Mundy: I came of age in the early 1980s, when reproductive rights was an almost defining ideological issue. The word “choice” really had one meaning: your position on what a woman could do with an unwanted pregnancy. I’ve written all my career about reproductive politics, including what turned out to be a controversial article about two deaf lesbian women seeking a deaf sperm donor, which introduced me to the field of bioethics. Then I wrote about how low-income people experience infertility in 2003 and learned how common infertility is and how hard people will work to have a child.

After that article I was having lunch with a reporter who was pregnant with IVF twins, and it was at that moment I realized the menu of reproductive choices had expanded enormously since I was in college. When you embark on infertility treatment, you face hard choices that scramble whatever preconceived notions you might had about the notion of choice.

RW: Do the questions raised by assisted reproduction make the abortion debate obsolete?

Mundy: I don’t think it will ever be obsolete in this country. In

RW: In your book, you suggest that some infertility doctors hide, in some sense, behind the mantle of “reproductive choice.”

Mundy: Of course there is a lot of variation among these doctors; some are very scrupulous, others less so. But yes, some have co-opted the concept of choice to justify making everything available, and leaving up to the patient important decisions like how many embryos to transfer [to the womb in an IVF cycle.]

RW: So what does the word “choice” mean now in the reproductive context?

Mundy: The concept is so widespread as to be meaningless. There was one moment during my reporting, when the director of a pro-life-oriented group called Snowflakes, which arranges embryo adoptions, talked about providing people with “as many choices as possible.” It was a beautiful example of how the pro-life and pro-choice positions become so intermingled on these issues.

RW: When you interviewed people who were facing hard choices — about whether to reduce a multiple pregnancy, for example, or a tell a child he or she was the result of gamete donation — did you find that many consulted with their religious traditions or leaders?

Mundy: I was at one fertility clinic, waiting to speak with a doctor, and I saw a woman, who was Catholic, cancel her appointment after talking with her priest, who advised her against being treated with fertility drugs. Of course the Catholic Church has more formal guidelines [on assisted reproduction technology] than most; they oppose IVF from the start as being unnatural and abrogating the realm of God.

I also talked to pastors who said in the course of their work people confide in them about the grief of experiencing lifelong infertility.

RW: In your book you talk with infertility doctors, patients, bioethicists and others who have thought deeply about the ethical issues of fertility medicine, but religious figures don’t appear much. Why is this? Are there no religious leaders up-to-date enough that they would have made an interesting interview?

Mundy: Yes, I would say so. I didn’t run across anyone who jumped out at me. A lot of official church bodies are being forced to grapple with reproductive technology now, most evidently in the area of stem cell research. They are trying to figure out how to think about the embryo, and some churches have weighed in.

RW: You describe how many couples are almost paralyzed by the question of what to do with their frozen embryos. If religious organizations all issued clear moral guidelines, would that help people make these tough decisions?

Mundy: People don’t always follow dictates of their church of course. The question is made more difficult because it’s so hard to donate embryos for research right now.

When patients go through this process, they become very attached to the embryos. It’s a very personal thing. So even if your church says it’s okay [to allow embryos to “lapse” or be donated for research or adoption,] that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s easy or it feels okay to you.

RW: Do you see a parallel here with descriptions of pro-life people who have, for whatever reason, found themselves seeking abortions? That personal experience can be so powerful as to override even religious belief?

Mundy: That’s right. What makes it so hard for people is that many if not all religions place a high value on family and family life. The Catholic Church might say IVF is wrong, but the church and the culture are simultaneously saying children are the greatest blessing. Those would be confusing messages to process.

I also talked to people who encountered religious prejudice. One woman used fertility drugs and conceived quadruplets, one of whom died and the other three of whom were disabled. She said sometimes when she went forth into her Texas community, people would say, “You got what you asked for in defying the will of God, because God intended you to be infertile.”

RW: Was there ever a moment in your reporting when you thought, “Maybe the Catholic Church is on to something in prohibiting IVF. Maybe we never should have let the genie out of the bottle?”

Mundy: No. What struck me most were the people who said, “No matter how hard it was, it was all worth it.” I don’t want to be Pollyanna-ish about it. There were certainly people, particularly with multiples, who said, “If I could go back and do it over again, I would do it differently.” But I do think it’s a good thing that three million children now exist who would not have existed if it were not for the science. I was trying to highlight the difficult choices, but I didn’t have the sensation that all of this is wrong or misguided.

RW: In one of your chapter titles, you call selective reduction the “best-kept secret” of reproductive technology. Why hasn’t the issue received more public attention?

Mundy: It’s not something people like to talk about it, if they’ve had a selective reduction. Unlike abortion, there are not strong advocacy groups mobilized on either side. The fertility industry really doesn’t want people knowing how often this occurs, and most of the doctors who perform it probably aren’t going to let a reporter spend time with them. But there is no shortage of medical literature about it. Just go onto Pub Med and type in “selective reduction” or “multi-fetal pregnancy reduction.”

RW: Does it strike you as odd how some fertility-related ethical issues — like partial-birth abortion for example — grab headlines, but other equally vexing issues — like selective reduction — don’t?

Mundy: It tends to come up when someone has, say, octuplets, or other high-order multiples, and it’s on the evening news. Sometimes the couple says, “We just couldn’t bring ourselves to do selective reduction.”

RW: Out of the many issues you discuss in the book, are there one or two you think are likely to become hot-button debates in the next few years?

Mundy: In this country, a lot of these debates are going to be carried out in state legislatures, because that’s where family law is made. Connecticut, for example, has voted for insurance coverage for IVF, and insurance companies can therefore limit the number of embryos transferred in IVF.

In the United Kingdom, there is a government agency to regulate assisted reproduction, and its decisions are often met with outcry and debate. You see assisted reproduction issues on the front pages of the newspapers there all the time. It’s just part of the public discourse. Whether or not people [in the U.K.] have been through fertility treatment themselves, everybody thinks they have a stake in these moral debates.

In the U.S. because [infertility treatment] is a private, profit-making branch of medicine, and it’s not regulated or funded in any high-profile way that would provoke an outcry, I don’t know whether the public discussion is ever going to crystallize. But something could always percolate up. Who knew that one of the first questions President Bush was going to have to deal with when he took office was federal funding for stem-cell research?

RW: So does the U.K. have it right?

Mundy: They have a more coherent policy than we do.

RW: Is that because they have a state-run health care system?

Mundy: After IVF first succeeded, in England, with the birth of Louise Brown, there were scientists who organized themselves and created charitable foundations to bring some coherence to the debate. They made a concerted effort to educate Members of Parliament, literally inviting them to look down microscopes at embryos. As one scientist told me, “That did a lot to persuade people that we weren’t making Frankensteins in the basement.” They made an effort to move the issue forward, and that doesn’t seem to have happened in this country.

Jul

30

If you’re looking for a summer-reading book that will both keep you up late at night turning pages and give you a shopping-list-long set of often-heartbreaking moral questions to ponder, then run don’t walk to get Liza Mundy’s recent book, Everything Conceivable: How Assisted Reproduction is Changing Men, Women and the World.

While reporters have covered aspects of the ethical dilemmas posed by assisted reproduction technology, such as parents struggling to decide what to do with unneeded frozen embryos, or some people’s discomfort with gay men become parents through surrogacy, or, of course, the question of women delaying childbearing, Mundy appears to be the first to pull together these disparate social trends and scientific advances to give a big-picture look. And as she pulls the camera back for the wide-angle view, Mundy reveals a host of bedeviling questions, which she deftly illustrates with portraits of the real people who are wrestling with them. Here’s a sample:

Are parents who have children using sperm or egg donors obliged to tell these children the truth of their conception and genetic history? If you say no, consider this story Mundy relates: A D.C.-area single mom uses a sperm donor to conceive twins, then finds out the woman across the street from her is also pregnant with twins — from the same donor! These sets of twins, who are genetic half-siblings, could be in the same class at the same school: Do they have a right to know that their potential friends or even, at some point, mates are in fact related to them?

On the flip side, Mundy describes the situation in the UK, where sentiment favoring children’s right-to-know runs high; anonymous sperm and egg donation is now prohibited. This law, however, has had the effect of drying up gamete donations — meaning, as Mundy puts it, some children won’t be born as a result — and pushing UK parents to seek anonymous donors in Eastern Europe. (And the word “donors” here belies the fact that in many countries, including the U.S., women can earn thousands of dollars for donating eggs.)

Should there be a limit on how many embryos fertility doctors transfer to a mother’s womb in the case of in-vitro fertilization (IVF)? If you feel like you don’t know enough about the topic to make an informed decision — well, that’s how many IVF-treatment parents feel when their doctor gives them five minutes to make the decision to implant one, two, three or more embryos.

The risk involved? A multiple pregnancy can seriously endanger the lives of not only the fetuses but the mother herself. Because would-be parents usually have to pay for expensive IVF cycles out of pocket, however, the pressure to transfer multiple embryos is intense. The result? A skyrocketing number of multiple births and a relatively new procedure known as “selective reduction,” in which a doctor ends the life of one or more fetuses to protect the lives of the remaining fetuses.

Mundy’s chapter on this topic, “Deleting Fetuses: Selective Reduction, ART’s best-kept secret,” is perhaps the most disturbing, as she follows several couples forced to choose between keeping all three or four fetuses — and running the risk of losing them all — or eliminating one or two of them. (A condensed version of this chapter also appeared recently in the Washington Post Magazine.) Mundy describes how one doctor decides which fetuses’ hearts will stop beating on the basis of their genetic health, position in the womb, or — gulp — sex.

It is a Sophie’s Choice nightmare to contemplate, especially when we read one parent’s comment that selective reduction is harder to deal with after the surviving fetuses/children have been born. Said one mother who had reduced her triplet pregnancy to twins: “You think: I could have ended up with one of these being gone, and the one that is gone could have been one of these.”

These are just several of the many dilemmas Mundy’s book raises, and while she offers no easy answers, she says the first step is clear: There needs to be a louder, more public debate on these complex moral issues. Her book is a perfect place to begin.

Coming Wednesday: ReligionWriter interviews Liza Mundy on whether the ethical questions of assisted reproduction technology make the abortion debate is obsolete, and how religious leaders are struggling to keep up.

Jul

25

“Some Days, I Feel Like a Barnacle:” The Pace Car of Religion News Blogging

July 25, 2007 | 2 Comments

When the Dallas Morning News’ award-winning religion section, one of the country’s only stand-alone faith sections, folded back into the rest of the paper in January, 2007, due to insufficient ad revenue, observers in the field worried about the decline of religion journalism. Wrote Martin Marty: “We have reason to shed a tear” because, in his view, content produced for the web tends to focus on “outrageous or attention-grabbing coverage,” thus sidelining the more complex religion topics.

Just a few months before the section folded, however, the religion team at the DMN, including long-time religion reporter Jeffrey Weiss, launched its own religion news blog, DallasNews Religion. Today Weiss is a main contributor to the blog, along with fellow religion reporter Sam Hodges and former religion editor Bruce Tomaso.

Just as the paper’s religion section was once an industry standard, so now its blog may be leading the way for print-based religion reporters, who, willingly or reluctantly, are beginning to blog.

ReligionWriter recently phoned Weiss to talk about journalistic integrity online, time management and the filter-feeder nature of blogging.

ReligionWriter: How did the blog get started?

Jeffrey Weiss: The editorial board of the Morning News started blogging three or four years ago – very gingerly, as a toe-in-the-water kind of thing. Last year, it became clear the religion section was going away. We decided, “Let’s do it.” It was something our bosses wanted us to do, and, frankly, it smelled like the future.

Jeffrey Weiss: The editorial board of the Morning News started blogging three or four years ago – very gingerly, as a toe-in-the-water kind of thing. Last year, it became clear the religion section was going away. We decided, “Let’s do it.” It was something our bosses wanted us to do, and, frankly, it smelled like the future.

RW: Were you positive about the idea at the time?

Weiss: I was reluctant because I knew it would take a lot of time. Was it going to be worth the effort? Would enough people be willing to be involved? Would we have enough material? I had no answers to those questions. But some of the energy that had been devoted to the section was now available for the blog, and, actually, it’s worked out pretty well.

RW: What’s your blog’s purpose?

Weiss: It has several. First, it gets information out to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to get to it easily. We post a very broad spectrum of stuff, from intensely local denominational meetings to Supreme Court decisions. Some days I feel like a barnacle: A barnacle sits on its pier, filters the water, pulls out the best stuff and eats it. In my case, I post it.

But we also do exclusive content. When I write a long story for the paper, I will have reported fifty pages of notes and used about five. So I post the best of the stuff that didn’t make the cut.

The blog is also about interactivity. It’s a way to have a conversation, especially with the regulars. We have probably half-a-dozen regular commenters; I think of them as the two old guys in the balcony of The Muppet Show, tossing out their opinions. Frankly, a lot of the comments aren’t that wonderful, but every so often, I’ll get a thoughtful one, where someone has taken the topic, processed it, and provided valuable new content. That’s when I think, “Boy, am I glad we’re providing a space for this.”

RW: Who do you see as your main audience?

Weiss: Ultimately, we have no way of knowing exactly who is clicking on. I know a lot of other religion journalists read it, along with denominational leaders, local pastors, and at least one chaplain in

. So we have people from all over the world, along with a local crowd.

RW: Do you pay much attention to your site statistics?

Weiss: I pay attention in this regard: the effort has to be worth it. Ultimately, we’re a business, and there has to be enough readers that our advertising department can attract advertisers, enough to justify my time. That doesn’t necessarily mean huge numbers. We’re trying to figure out: Are there things we can do to boost the numbers?

RW: Can you tell us how many visitors you get each month?

Weiss: I’m not going to do that, but I can say the numbers are much larger than they were six months ago, and they continue to creep up.

RW: How do you plan to boost traffic?

Weiss: We are trying to put key words in the headlines and make the first line really substantial, because Google is starting to index the blogs a lot better. I’m thinking more strategically; now, for example, our blog is cross-posted at [the WashingtonPost.Newsweek.Interactive multi-contributor blog,] On Faith.

RW: Do you feel like you’re in a new field now — online journalism?

Weiss: Five years from now, the distinction between print and online won’t make any difference. Am I an online journalist? Of course. Am I an offline journalist? I’m that too. Are their differences? Yes, there are. The voice I use on the blog is different from the voice I use for the front page of the paper.

RW: How’s your blog voice different?

Weiss: It’s looser, much more conversational. I’ll use Internet abbreviations like NYTimes; I’m much less attentive to AP style. I am, however, pretty careful about not expressing opinions in controversial matters. I might write that something is “interesting,” and you’ll get analysis out of me if I believe something is illogical. But you’ll never find me writing, “I believe abortion is right or wrong.” But even there, the line is a lot blurrier than it was even five years ago.

RW: Is blogging, at the end of the day, all about opinion?

Weiss: There is no predicate to the sentence that begins “blogging is all about….” Blogging is whatever the blogger wants it to be. There is plenty of straight journalism blogging out there; look at Romenesko. Is that about opinion? It’s a link-o’-links. If there’s an opinion expressed there, it’s: This is what Romenesko thinks journalists ought to look at. Blogs ought to be giving you something you don’t get in dead tree content. But whether it is opinion or analysis or just additional content, it depends on the blogger and the audience.

RW: You don’t feel badly that the blog is not more personal or point-of-view driven?

Weiss: It probably does need more voice. The convention of online writing and reading is voice-ier than dead tree. I happen to like that; I find that somewhat liberating. But writing on a blog does not mean you give up the conventions of journalism.

RW: How do you manage the time pressures of blogging?

Weiss: If you’re not careful the blog will eat you alive. You have to be aware of what your responsibilities are and what your bosses expect of you. There are time when I have to tell myself, “Stop now. Go back to the story you’re supposed to be working on.”

On the other hand, an awful lot of what we post is stuff I would have been looking at anyways, like interesting things in my e-mail in-box. I figure I do an hour or an hour and a half a day on the blog, sometimes more.

Today, for example, there are three Supreme Court decisions that have religion angles. In the old days, when we had the religion section, I might have read the decisions and done a piece on them. But the Morning News, like most other newspapers, is doing less national news. So I might instead include the decisions in our blog’s weekly newsletter,

RW: If you had to break it down, what percent of your time goes to blogging?

Weiss: It’s hard to say, but maybe one-fifth.

RW: Do you feel you should be paid more for a 20-percent increase in your work?

Weiss: Don’t we all? You need to make sure you’re in tune with what your boss wants.

RW: What does that mean?

Weiss: If you’re expected to produce a certain amount of content for the dead tree, then your boss has to understand that blogging doesn’t come on top of that, it comes out of it.

RW: Will the DMN blog look the same in two years or five years? What’s ahead?

Weiss: I sigh deeply, because our horizon is so close. You might as well ask me how I think newspapers will look in fifty years: I have no idea. We will be trying some different things in the nearer future. We have pictures now, maybe we’ll have videos. We’ve talked about having regular features. You look around at other blogs, and ask what they are doing that you like. I’d be surprised if our blog looks the same in six months or a year. But exactly how it’s going to change? I have no idea.

Related Content from ReligionWriter:

“Blogs: Top Religion Reporter Says Blogging is Exciting, Draining and Obligatory”

“An Independent Muslim-American Press? Texas Entrepreneur is Making It Happen”

Jun

11

An Independent Muslim-American Press? Texas Entreprenuer Is Making It Happen

June 11, 2007 | 3 Comments

As a father of two and a full-time real estate developer in Austin, Texas, Shahed Amanullah has also been able to squeeze in a side-project over the last few years: opening up the American Muslim community to debate and criticism.

As a father of two and a full-time real estate developer in Austin, Texas, Shahed Amanullah has also been able to squeeze in a side-project over the last few years: opening up the American Muslim community to debate and criticism.

After 9/11 attacks, the American-born Amanullah, now 39, watched his community “circle the wagons” under a barrage of sometimes hostile attention and decided to create Altmuslim.com, a news and opinion site that would allow Muslims to discuss their own issues, on their own terms.

Although Altmuslim.com has been successful, now receiving more than 8,000 unique visitors a day and sustaining operations through a revenue-generating sister site, Zabihah.com, Amanullah is still not satisfied. In an April, 2007, column, “Western Muslims Need a Fourth Estate,” he called for the creation of an independent Muslim press in the U.S., to

explore the religious, cultural, and political plurality within the Muslim community, hold Muslim advocacy groups, businesses, and institutions accountable for their actions, present a forum for the civilized discussion of underrepresented or even controversial opinions, and increase the ability of ordinary Muslims to defend their faith beyond bumper-sticker platitudes.

Amanullah’s forth-right embrace of debate and analysis is winning him an increasing amount of national attention. Named one of ten “young visionaries” last month by Islamica magazine, he was also tapped this month by Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff to advise the department on fighting terrorism.

ReligionWriter spoke with Amanullah about his impatience with “whitewashed” media articles, his favorite reporters, and his plan for putting to rest the question, “Where are all the moderate Muslims?”

ReligionWriter: Your “Fourth Estate” article has gotten a lot of attention in the American-Muslim blogosphere. Did that surprise you?

Shahed Amanullah: Yes; I didn’t think it would be news to people. Every community has a degree of internal dialogue and discussion that is healthy, and I’ve been struck by how little of that goes on in Muslim community. There’s too much emphasis on enforcing orthodoxy as opposed to respectful debate.

Shahed Amanullah: Yes; I didn’t think it would be news to people. Every community has a degree of internal dialogue and discussion that is healthy, and I’ve been struck by how little of that goes on in Muslim community. There’s too much emphasis on enforcing orthodoxy as opposed to respectful debate.

In the center of this storm of politics and media, we’re like a little raft tossed up on the big waves. Issues are thrust upon us; we never set the agenda. When other organizations set the agenda for us, it has a very limited scope: civil liberties or foreign policy. We constantly have to respond to things thrown at us in unfavorable terms, like the issue of extremism. A great example is the “Where are the moderates?” refrain we’ve heard since 9/11. This silence happens because there is no articulate voice. Local Muslim newspapers say, “It’s not our issue.” National Muslim organizations say, “We want to talk about civil rights instead.” There’s nothing in the middle.

RW: Which issue do see as more important: promoting dialogue among Muslims or shaping the media agenda in the non-Muslim sphere?

Amanullah: I don’t separate the two. Part of the message we need to get out to the larger media is that we’re having this discussion, that there is dialogue within the Muslim community about “What is our vision? What are our values as Muslims in America?” The wider media needs to see this conversation is happening. Because when they don’t see it, they start setting the agenda: “Muslims need to start worrying about extremism in their mosques.” If they know that dialogue is already happening, then they can take the cue from us.

RW: Do you feel mainstream journalists aren’t tapping the right sources in the Muslim community? That maybe they rely too much on national organizations like ISNA or CAIR?

Amanullah: I don’t blame journalists; they don’t have anywhere where else to go. I also don’t blame [CAIR spokesman] Ibrahim Hooper Ibrahim Hooper for his interviewing style - his job is to be a media bulldog. His job is not to provide insight that may reveal weaknesses in our community. That job belongs to analysts of the Muslim community. And right now, most people who set themselves up as media-ready analysts on Muslim affairs are not from our community.

RW: Who are you referring to?

Amanullah: Professors, whether Muslim or not, who are in their ivory towers and removed from the community. Journalists who have taken up Islam as their thing, whether it’s Tom Friedman or Daniel Pipes. So many non-Muslims put on the “Islam expert” hat, and they can get away with it, because there isn’t a Muslim alternative who says, “I’m here in the community, and I have the credentials to be authoritative.”

RW: But newspapers don’t necessarily assign evangelical reporters to cover evangelicals - and maybe they shouldn’t.

Amanullah: When you create a fourth estate, you’re not creating cheerleaders. You’re creating people who over time are going to have a reputation of being objective and analytical, critical but also giving credit where credit is due.

RW: Almost every day there are positive, Islam 101-type articles, especially from small-town papers, with headlines like, “Muslims draw closer to God during Ramadan.” Is it really fair to say Muslims are misrepresented in the media?

Amanullah: Those PR-type articles are problematic in their own way. Unless you properly deal with the larger issues, the benefit of these pieces won’t sink in for the average reader. At the national level, you get more contentious articles, assigning blame to all of us for what some of us do. What is missing are articles, either at the local or national level, that say, for example, “Here’s an interesting positive trend in the Muslim community,” acknowledging that we have issues but also that we recognize and deal with them. I don’t want to be patronized by local media or condescended to by national media.

RW: A common thread among the responses to your “Fourth Estate” article was that creating an independent Muslim media will ghettoize the community. Better, they say, for Muslims go to into mainstream journalism. What’s your response to that?

Amanullah: The role of the Muslim media would be to start the dialogue on important issues. At a certain point that percolates up to the national media. Also, it’s a training ground for analytical thinkers, whether they want to continue on into mainstream journalism or Muslim leadership.

RW: If you had 20 journalists sitting in front of you right now, who were going to cover Islam in the next few months, what would you tell them?

Amanullah: Don’t miss the very dynamic debates that can and do happen within the Muslim community. It’s not enough to report on the Muslim community as a zoo specimen: “Let’s see what happens when we poke it here.” Get into the Muslim community at a local level and find out what the debates are.

We’re at a unique time in American Muslim history, when American Islam is still being defined. When people think of Muslims as monolithic, it feeds into the impression that we’re a bunch of sleeper cell operatives. But if you can say, for example, “There’s a big debate right now about intercultural marriage,” that shows a dynamism, and that makes us human.

RW: In your view, who are the best reporters right now covering Islam in America?

Amanullah: At the metro level, Matthai Chakko Kuruvila at the San Francisco Chronicle is head and shoulders above the rest. His attitude toward covering the Muslim community is fascinating; it’s like the difference between looking at a gorilla in a zoo and being Jane Goodall, actually getting in there. At the national level, I’m fairly happy with Laurie Goodstein at The New York Times. Carla Power at Newsweek has done a really good job, and she’s been working on it for a really long time; I first talked to her in 1998. Neil MacFarquhar at The New York Times, generally, is trying to get in at the lower level as well. I really like the reporter I deal with here at the Austin American Statesman, Eileen Flynn.

RW: One could argue the Muslim press right now is looking great. We have altmuslim, first of all. We have Islamica, Illume, Azizah, Muslim Girl and others. Would you agree?

Amanullah: A community of our size should have had an independent media a long time ago, and now we should have a larger one. Of the media outlets you mentioned, only Islamica has any full-time staff that I’m aware of. We’re not talking Christian Science Monitor here. Look at the Jewish community, which has a vigorous free press. Or recently arrived immigrant communities, like the Filipino and Chinese communities — they have many more fulltime journalists. Why don’t we?

Jun

4

The Holiness and Horror of Amish Life: Journalist Joe Mackall Writes about His Extraordinary Neighbors

June 4, 2007 | 2 Comments

Joe Mackall has lived a mile away from the Shetler family for more than 16 years, driving Mary, Samuel and their growing family of nine children to the doctor when needed, sharing the family’s grief over a child’s death, and gradually bridging the divide between his own “English” (non-Amish) culture and their insular world of farming and family. Such friendships are rare, particularly because the Shetlers are members of the most conservative Amish sect, the Swartzentrubers, who eschew even reflective “caution” signs for their buggies and the practice of rumspringa, popularized by the 2002 documentary, Devil’s Playground.

In his new book, a mixture of memoir and reportage, Plain Secrets: An Outsider among the Amish, (Beacon Press: June 15, 2007,) Mackall invites readers into the Shetler family to consider what Mackall describes as the “holiness” and “horrors” of Swartzentruber life.

After the Shetler’s daughter, Sarah, dies of brain cancer, for example, Mackall writes of going to view the body, laid out on a simple board in her church clothes, with an elderly man holding a kerosene lamp over the girl’s face:

Whether it was the glow of the light or the play of the shadows, or the old Amish man’s wizened face, or the tears of strangers, or just that there were so many people huddled in a home to comfort two young parents, to commemorate a life and to commiserate over a life lost, I felt at that moment that there was something beautiful and holy at the center of Swartzentruber Amish life.

But when he’s driving in his car on a nearby road, coming upon a Swartzentruber buggy with two children playing the back, he is sickened to watch one child fall out the back of the buggy onto the asphalt. Mackall writes frankly about his sense of outrage:

Does God really care that you drive a buggy and I drive a car? Is sticking with your sacred buggies more important than the sanctity of human life? Can’t you take care of your children?

ReligionWriter spoke with Mackall this week about his decision to risk his friendship with the Shetlers to write this book; what he would do if a Shetler child left the Amish and sought his help; and how it feels to take a buggy ride to Home Depot.

ReligionWriter: You have such a deep and complex relationship with the Shetler family. Why did you decide to put the story into words and publish it?

Joe Mackall: I knew it was going to be complicated, all the way. I did not want to endanger my relationship with the Shetler family, or do them any harm. But it was one of those things where, 30 years from now, I would be scratching my head, saying, “Why didn’t you write that book?” Ultimately, it was impossible not to write, mainly because of how fascinating they are, and I knew I was getting a look inside that not many people have gotten. I could never live that way, and there are some horrors about living that way, but I also admire it tremendously. The Shetlers are also an exceptional family, whether they were Amish or English or whatever—just the kind of family you like to hang out with.

RW: At one point you ask Samuel to trust you as you write the book. Yet even you doubt whether you should be trusted, knowing that a book, once it’s published, can have a life of its own. Were there moments when you thought, “My relationship is him is too important; I can’t write this?”

Mackall: I didn’t talk to them about a writing book until knowing them for more than 10 years. Samuel knew I am a writer, and that I was very curious the community; I was always asking him a million annoying questions. After the manuscript was finished, before it went to the publisher, Samuel and Mary read it, and then the three of us sat down and talked about it. I ended up taking out two things, which I thought were pretty innocuous. The things I thought would be more incendiary, they didn’t have a problem with. But when Samuel [was elected by his community to become] a minister, that’s when I thought we were going to be in trouble. As a minister, everyone is watching him, including the bishop [who leads the community.] Samuel worked with me behind his bishop’s back. That’s not uncommon among the Amish I know: there’s a side shown to the bishop, and a side shown to everybody else. I don’t think it’s hypocritical; it’s the way you might behave with your boss, as opposed to when the boss is not there.

RW: In becoming close friends with you, let alone authorizing you to write a book about the Swartzentrubers, Samuel risked being officially “shunned” or otherwise reprimanded. Why did Samuel go along with you, when apparently so much was at stake for him?

Mackall: I still ask myself that question. When I pushed him, he gave me two reasons. One, it’s just because I was the one asking. Not because I’m such a great guy, but because they know me and trust me, and we’ve been through a lot together. Two, the Amish know the way they are portrayed in the “English” world, like the 20/20 story on abuse in the community. A lot of people in rural Ohio don’t like them, asking, you know, “Why are their horses sh-ing in the road?” Samuel said he was hoping my book would show the Amish in a good light. I told him I was going to have to show them in the light that I saw them.

RW: It seems surprising Samuel would have that media awareness. Why should the Amish care how people view them?

Mackall: They do have to be separate from the world. But it’s in their best interests not to have an antagonistic relationship with the world. A county could say: “No horse droppings on the road.” If English people wanted to make life miserable for the Amish, they could do it. They want to get along with the English world, even though they’re separate of it. Some of it, though, might be just a non-Amish, human need to see the group you belong to portrayed in a good light.

RW: You write about Jonas, Samuel’s 18-year-old nephew who leaves the Amish and faces a lot of hardship in the English world. If you’re ex-Amish, having a trusted English friend makes that transition so much easier. But that’s exactly what the Swartzentrubers doesn’t want: an easy transition.

Mackall: That’s why [Swartzentruber parents] are so afraid to have English friends. After a while, their kids might say, “If my parents like them, and they’re not Amish, then maybe you don’t have to be Amish to be good.” It’s such a tightly woven fabric, any time they let someone like me in, it’s not as strong as it was before I came.

RW: In the book you ask yourself, what would you do if one of the family’s daughters left the Amish and sought your help? What’s the answer to that question?

Mackall: I hope to God I’m not faced with that. It would be a horrible choice. But [if a Shelter child did leave the Amish, they] probably would come to us, because they’ve known us — most of them — for their entire lives. It would be hard for us to turn our backs on a Shetler.

RW: Given your 16-year relationship with the Shetlers, how did you narrow down which experiences to write about: for example, your description of you and Samuel riding the buggy to Home Depot?

Mackall: When I starting working on the book, I was at the Shetler’s farm morning noon and night. Samuel is constantly working, so you have to be at his side to interview him - he’s not just going to sit down and talk to you. When I had an opportunity for a buggy ride, I jumped at it because I knew I’d have a captive audience.

RW: But going along with him in the buggy put you at risk.

Mackall: A buggy is a scary thing to ride in. When you’re on small road, at dusk, or in the fall, it can be just beautiful. But on bigger roads, with cars flying by; I imagined jumping out [in case I needed to save myself.] Buggies are no match for cars in an accident. I have full confidence in Samuel as driver, but there are just too many variables: the horse, the car, the noise, the buggy itself. It’s not an ideal way to travel. Maybe it was when everyone drove a buggy but not now, especially because the Swarteztruber won’t even put a reflective “Slow Moving Vehicle” sign on the back of their buggies.

RW: You critique the way Americans look at Amish, either reviling them as backwards or idealizing them. What was your impression of the coverage of the Amish school shooting?

Mackall: Most Americans — non-Amish people — were amazed at the ability of the Amish to accept what happened and forgive the killer. But that forgiveness is not exactly how we think of forgiveness. It’s more like they looked right through the tragedy to the fact that it was God’s will. Since it was God’s will, then of course they had to get close to the woman whose husband did it. Amish people don’t like to be on camera, and most news people didn’t seem to give that much thought. I thought growing up Catholic was tough; the Amish have so many more rules, so an outsider is bound to step in the middle of that.

RW: Given that the Amish sometimes represent a lost rural past for Americans, it seems like some English would want to become Amish. Do they accept converts?

Mackall: They do. I could walk in there and say I wanted to be Amish, but I would have to go through probationary period for a couple of years before being baptized. Converts really have to prove that’s the life they want to live. It’s not like being a Hare Krishna — walking around an airport with flowers is a hell of a lot easier than becoming Amish. Forget the religious stuff: the day-to-day life is rough.

RW: Is Samuel going to appear with you at any publicity events?

Mackall: No, but that would be funny. He wants some deniability. I’ve given him a book already; I’m sure he’s hidden it in his house so no other Amish can see it. He’s probably gone as far as he’s going to go. And that’s farther than any other Swartzentruber has gone, unless they’ve left.