“To Make an Enemy of 500 Million People is Ludicrous”

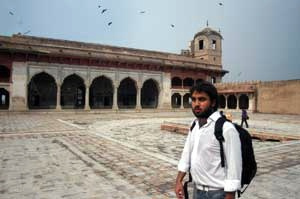

In the last post, ReligionWriter was speaking with video and text blogger Amar Bakshi about the religious ideas he found while traveling in Britain.

ReligionWriter: A poll this month found that Osama bin Laden has a 46% approval rating in Pakistan, making him more popular than Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf (38% approval rating among Pakistanis) and U.S. President Bush (9%.) To most Americans, those numbers for Bin Laden seem absolutely horrifying. What would you say to help Americans make sense of them?

To some of the people I spoke with, Osama bin Laden represents slap in the face of

In Pakistan, as in many countries besides the U.S., historical memory, and the mythologization of that memory, is very powerful; Pakistanis well-remember America’s involvement in the rule of [former military leader] Zia ul Haqq. Ironically, they are objecting to the radicalization of Islam and the loss of liberty that his rule entailed — in a convoluted way, that is associated with America in the minds of Pakistanis. There are similar analogies in Iran.

RW: Is anyone who supports Osama bin Laden necessarily a violent enemy of America? Is it possible to humanize that bin Laden supporter? Is there any common ground to work with?

Bakshi: The whole pursuit of “How The World Sees America” — and for some people, I’ve learned, my approach is quite controversial — is to humanize these guys. How are you going to say 46 percent of a country of 160 million are fundamental enemies? That’s ridiculous. If you go to other countries, the numbers are just as staggering, if not more so.

To make an enemy, in our minds, of 300 or 500 million dispersed people is ludicrous. So you’re going to have to humanize. I can see the headline: ‘Humanizing Bin Laden Lovers.” Put that way, you can just dismiss the idea, but that’s far too simplistic.

There is a huge spectrum of what that support actually means. Would any of these guys lay down their lives for him? If you ask that in a poll question, I don’t think the number would be high. So what does it mean to them to support someone like bin Laden? And what is it they are searching for? These types of questions usually have very personal answers. That’s very much what this project is about: what are those personal answers?

RW: Do you mean everyone has a story like “a CIA agent killed my brother?”

Bakshi: Each act that takes place affects 100 people around that act. Social networking thought might help here. When one person dies in

Then, of course, anti-Americanism is very much exploited by political parties, by imams wanting more power or prestige, or in organizations where anti-Americanism is a way of expressing belonging. So you might start with a rational reason for disliking America — maybe a CIA agent really did kill your brother — but this drumming up of hype can quickly lead things to spiral into the irrational.

There are two things at work here. First, we have got to figure out what policies of ours might be dangerous for us in terms of perceptions in the long term. I think that’s an important consideration, and one that we can control. Then we have to see some things for what they are: for example, political infighting in which orthodox people attack moderates by claiming they are pro-America. Really that has nothing to do with America, it’s really about moderates and extremists battling each other within their own society.

RW: Tell us a little about your own religious and cultural background. What sort of Hinduism were you raised with?

Bakshi: I went to Episcopal school, St. Albans, where I was on the vestry. My mother is a spiritual woman, but no one in my family is particularly religious. To me, religion is a way of ordering your spirituality, of disciplining it. The idea is a certain practice gets your spirituality richer or better.

I have been free to dabble in a lot of different things and read a lot of books, both as literature and for teasing out how to live life. In terms of what practice I want to use to discipline my spirituality, I haven’t decided yet, but I’m not opposed to picking one eventually.

If anything, my family is Hindu, but there are Muslim influences as well, and of course I went to Christian school, and my mother tried to send me to Hebrew school -

RW: Hebrew school?

Bakshi: I was young, and at the time, my mother thought it was a just beautiful language, with beautiful stories, and she always dreamed of going to Jerusalem. She still does.

RW: You were born and raised in Washington D.C. Before you went to India for your blog, had you been to there before?

Bakshi: Growing up my mother never really wanted me to see India or learn Hindi. My parents had just recently migrated to the U.S., they were struggling to fit in, and my mother was fighting her own gender war to define herself as a physician, and she thought Indian culture didn’t help her in that. But when I was 15 I went back to India when my mother set up a local scholarship for a girl in Mysore, where she was from. I got really interested in local crafts people and set up something called Aina Arts, which links crafts people up with art markets.

RW: You are often mistaken for a Muslim. How has that experience affected you and your reporting?

Bakshi: One reason I don’t want to talk much about my religion online is that I love being mistaken for any number of things. In Latin America, I’m taken for Latin American. When I introduce myself to Muslims, I’m assumed to be Muslim, and Hindus assume I’m Hindu; I know enough about each to hold my own.

I go to a lot of Muslim services around the world, wherever I am. It’s a great way to connect and meet people, and I don’t feel badly doing it.

RW: You mean you would go to Friday prayer at a mosque and pray yourself? As part of your reporting for the blog?

Bakshi: Yes. (Laughs.) I have gone to Friday prayer and prayed, often out of sign of respect; I would be with a bunch of people who were going to pray, and it seemed rude to say, “I’ll wait outside.” In high school, I said the prayers every day, and I wasn’t Christian. I was head prefect of my school for a while, and at every ceremony I had to give a prayer, which I ended with “Amen.” One teacher told me it was just a sign of respect.

So that’s how I interpret it. [Blending in] helps me meet a lot of people, and I earn a lot of trust as a result of being ambiguous. I have no hesitation about that, because ultimately I think it’s foolish for there to be divides on the basis of religion, and I’m perfectly happy moving between them.

RW: So you go to a madrassa in South Asia and act like a Muslim, salaam aleikum and all that, and later they find out you’re not officially a Muslim: What happens next?

Bakshi: I never lie. If someone asks me “what are you,” I say exactly what I told you: my parents are Hindu but they are spiritual; I have devout Muslim and Sikh ancestors not that far back; I went to a Christian school, and basically I haven’t decided for myself yet.

I’ll be around the most hard-core Muslim guys you can imagine, and all they’ll say to me is:”Look, brother, this is not a good way to be, you have to choose.” They won’t say, “You snuck into our mosque, how dare you.” I’m happy to have them present to me the values they find in their faith. If anything, that’s when their passion really comes out.

Comment by Proud on 19 September 2007:

Great interview man.

Comment by Erica on 25 September 2007:

Hey right on. That sounds pretty intelligent. I’m often startled at the lack of intuition displayed by a great number of people on multiple sides of the issue. I’m glad to see that you are following up in a more moderate path, as not only americans, but lots of people who are middle class or wealthy enough to be isolated from other opinions, can forget this pretty easily. (I’m a people watcher too, and not only that, people who blend go to the best parties! )

Comment by Hindu Nationalism will bring us victory on 2 October 2007:

Quite interesting.

But you have not expressed your thoughts on Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism the muslims create where ever they become majority or in large numbers.

Iam a hindu living in India.